Where do Christmas trees come from? Or, since we know they come from the forest (or farm), a better question might be: Why do we decorate our homes with evergreen trees (or replicas of them) in the days leading up to Christmas?

There are lots of stops on the historical train ride of myths and facts that make up the origin story of the Christmas tree. Much of the speculation--including the myth about Martin Luther setting up the first one--has no basis in fact. We know that Romans brought tree branches into their homes in the wintertime. It's also clear that folks in northern Europe were decorating trees when Christian missionaries arrived there in the early centuries of the first millennium. But the clear historical link between decorated evergreen trees and the celebration of Christmas is difficult to pin down.

So let me add a bit to the myth-making by sharing one possible answer: the paradise tree. In medieval Europe most people did not learn about the Bible from reading it. Even if someone was among the small elite group of literate folks, books were expensive and rare. People instead learned about the main stories of the scriptures through miracle plays that enacted the major parts of the story. These plays, often performed on December 24th, began with the first chapters of Genesis, starting with Adam and Eve and their unfortunate encounter with the serpent and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The performing troupe would bring along a real tree, decorated with fruit, as a prop for the actors. Later in the play, as the history of salvation proceeded through the time of Moses and the prophets, the tree would take on other functions until the plot reached the life of Jesus. At the end of the performance, the tree's fruit of temptation would be replaced by Communion wafers, and the people would be invited to celebrate the sacrament.

Apparently the miracle plays on Christmas Eve became a big deal. Everyone would turn out for these events, including less reputable people who trafficked in the vices that emerge when crowds gather. Thanks to these nefarious elements, the plays were eventually banned, but many people held on to the tradition of decorating paradise trees by bringing them into their homes. (Maybe that was even a subversive act, done on the down-low, out of sight of the authorities.) Their ornaments were based on the tree's decorations from the plays -- round balls were like fruit, and cookies resembled wafers.

Is any of that true? It's nearly impossible to know for sure. But it's a great idea to link Christmas with the Garden of Eden. God sent the Son, who was Jesus the Christ, to save us from the effects of the fall. Human beings entered into sin through an encounter with a tree, and Jesus freed us from sin by hanging on a tree. The church used to celebrate the "birthday" of Adam and Eve on Christmas Eve, just a day before the birthday of the "second Adam." Our two human ancestors were created by God, but Jesus--the uncreated God who was there when creation was spoken into existence--was born by a woman so that the plotlines of our own sin-filled stories could be reversed. Thanks to this work of God, we can forever enjoy the fruit of new trees, which will always be in season in the age to come (Revelation 22). At that time, completely freed from the consequences of sin and death, we can always eat the fruit of the Tree of Life in the presence of the ascended Christ.

Saturday, December 24, 2016

Saturday, December 17, 2016

What is the Christian Year?

Christians think of time differently. From a worldly standpoint, all of our plans and meetings drive us to one predictable end point--the grave. To put it bluntly, appointment calendars and smartphone reminders are nothing more than tools for marking off the days and hours that remain until our deaths. Christians, however, follow a different storyline--one of resurrection, which was revealed to us through the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. This places us in a different relationship to time, pointing to an extraordinary end goal--one in which creation itself is healed by being remade. The liturgical calendar is a reminder that, while Christians still (temporarily) inhabit the world’s time, there is another reality at work, guiding and shaping God's resurrection plan for the entire cosmos.

The circle to the right provides a visual summary of the seasons of the Christian calendar. Each one reminds us of some aspects of God's greater salvation purposes:

|

| From thirdrva.org |

The circle to the right provides a visual summary of the seasons of the Christian calendar. Each one reminds us of some aspects of God's greater salvation purposes:

- Advent: Remembering Christ's first coming and anticipating his second.

- Christmas: God, in the form of the Son, took on flesh.

- Epiphany: Jesus's earthly ministry, including his baptism, revealed that he is God.

- Lent: Jesus goes to the cross.

- Easter: Resurrection -- the promise of all things being made new.

- Pentecost: The Holy Spirit is poured out on the church as a fulfillment of Jesus's promises.

Saturday, November 12, 2016

Veterans Day and Moral Injury

The conflict on the western front of World War I ended at 11:00am on November 11th, 1918 -- the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. Since November 1919, this day has been set aside as a time of remembrance of that war by the nations who fought together -- the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, France, and many others. It is still called Remembrance Day in most

other countries, but the US changed the name of its holiday to Veterans Day in 1954. In the wake of World War II, the government wanted to honor all veterans -- not just the ones from the first World War.

Veterans Day is a civic holiday, and churches may or may not observe aspects of it during their services. Whether or not remembrances show up in the worship of the church, there are things that congregations should understand and consider doing as a response to those who serve and have served in the armed forces.

Most importantly, American Christians should understand the term "moral injury." Not all the wounds that a veteran may suffer in conflict are visible. Human beings are not hard-wired to harm others -- it takes training to prepare for war, and even the best mental preparation might not be enough to cover the damage to the psyche that comes from witnessing and participating in violence. Thankfully, our society is more aware of PTSD, including its symptoms and effects. However, the damage that war can cause in the soul can take additional and wider-ranging forms. Healthcare professionals are increasingly using the phrase "moral injury" to talk about what can happen to soldiers.

Here is what Michael Yandell, a veteran, wrote for The Christian Century (quoted in this article in Christianity Today):

Listen. Military service is tough. Combat is not always a simple "us-versus-them" conflict. Soldiers have to make complicated, quick decisions on the battlefield, often with limited information. Many veterans feel like they made mistakes and carry regret. If you can just listen to their stories, without judgment, that can go a long way toward healing.

Lament. The scriptures are full of verses that describe human disappointment, fear, and longing for healing. Veterans might have sincere questions about what God is doing in the world, or they might question the very nature of a god who allows violence to happen. Jeremiah 4:21 says: "How long must I see the battle flags and hear the trumpets of war?" Psalm 22:2 honestly calls out: "O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest." These laments are helpful in the process of healing, and churches need to provide spaces for these honest feelings to come forth.

The most devastating aspect of moral injury is how it separates its victims from those who love them. Many veterans who question their service (or their God) feel like they cannot open up to others, even to their own families. Churches can provide a gift to veterans by helping them break open that isolation and loneliness.

|

Joseph F. Ambrose, a WWI vet,

was 86 years old when this photo was

taken in 1982. The flag is from his son,

who was killed in the Korean War.

From Wikipedia.org.

|

Veterans Day is a civic holiday, and churches may or may not observe aspects of it during their services. Whether or not remembrances show up in the worship of the church, there are things that congregations should understand and consider doing as a response to those who serve and have served in the armed forces.

Most importantly, American Christians should understand the term "moral injury." Not all the wounds that a veteran may suffer in conflict are visible. Human beings are not hard-wired to harm others -- it takes training to prepare for war, and even the best mental preparation might not be enough to cover the damage to the psyche that comes from witnessing and participating in violence. Thankfully, our society is more aware of PTSD, including its symptoms and effects. However, the damage that war can cause in the soul can take additional and wider-ranging forms. Healthcare professionals are increasingly using the phrase "moral injury" to talk about what can happen to soldiers.

Here is what Michael Yandell, a veteran, wrote for The Christian Century (quoted in this article in Christianity Today):

Repairing this kind of damage takes time and the care of professionals. While rehabbing someone may require more than a single congregation can provide, local churches have a role to play. Here are a couple (check out this article for more):For me, moral injury describes my disillusionment, the erosion of my sense of place in the world. The spiritual and emotional foundations of the world disappeared and made it impossible for me to sleep the sleep of the just. Even though I was part of a war that was much bigger than me, I still feel personally responsible for its consequences. I have a feeling of intense betrayal, and the betrayer and betrayed are the same person: my very self.

Listen. Military service is tough. Combat is not always a simple "us-versus-them" conflict. Soldiers have to make complicated, quick decisions on the battlefield, often with limited information. Many veterans feel like they made mistakes and carry regret. If you can just listen to their stories, without judgment, that can go a long way toward healing.

Lament. The scriptures are full of verses that describe human disappointment, fear, and longing for healing. Veterans might have sincere questions about what God is doing in the world, or they might question the very nature of a god who allows violence to happen. Jeremiah 4:21 says: "How long must I see the battle flags and hear the trumpets of war?" Psalm 22:2 honestly calls out: "O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest." These laments are helpful in the process of healing, and churches need to provide spaces for these honest feelings to come forth.

The most devastating aspect of moral injury is how it separates its victims from those who love them. Many veterans who question their service (or their God) feel like they cannot open up to others, even to their own families. Churches can provide a gift to veterans by helping them break open that isolation and loneliness.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

How to Vote

A couple of months ago I saw comedian Ted Alexandro open for Jim Gaffigan in Greensboro, North Carolina. He joked that we should all vote in this election, for the 45th and final President of the United States. Don't we all feel that this campaign has been like a very long Going-Out-of-Business sale? How do we vote in a time of cynicism and despair?

The Bible offers little practical guidance about democratic elections. None of its authors had the privilege of voting for their leaders -- they were stuck with the dictators, kings, and emperors that they were given. Since voting is relatively new in human history, we have to dig into the scriptures for guidance on how to cast our ballots today.

Psalm 72 and a Virtuous Leader

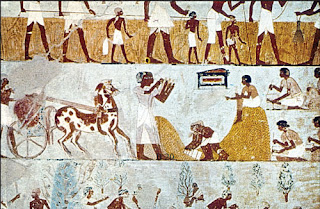

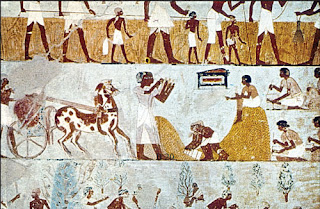

Let's start with the qualities of a good leader. Even if the people of Israel did not get to choose their own king, they understood what made up an effective government. Psalm 72 specifically names some of the virtues we all long for in a leader, then and now. For one, a good leader watches out for all the people in the land: the poor (verse 12), the weak (verse 13), and the oppressed (verse 14). Meaning, a virtuous leader does not choose a certain group of people to protect and care for -- those who voted a certain way, those who are related to certain others, or those who earn a certain amount. A king who governs rightly provides care for all people by reducing violence (verse 15), and we will see the very environment respond favorably: "May there be abundance of grain in the land; may it wave on the tops of the mountains" (verse 16). Granted, a human ruler cannot make it rain, or cause the sun to shine. But the story of Joseph in Egypt (Genesis 41) shows that a wise leader can indeed prepare for hard times, saving and storing supplies for those inevitable seasons of drought and famine. In addition, a leader who protects the poor also protects the land -- many recent studies have shown a strong connection between poverty and environmental degradation.

Joseph in Egypt (Genesis 41) shows that a wise leader can indeed prepare for hard times, saving and storing supplies for those inevitable seasons of drought and famine. In addition, a leader who protects the poor also protects the land -- many recent studies have shown a strong connection between poverty and environmental degradation.

Have these qualities from Psalm 72 helped you decide? Are you clear on whom to vote for now? Or do the candidates all seem to fall short according to these standards? Well, here is some advice to consider before, during, and after you head to the polls.

Before you vote: Pray

The Book of Common Prayer provides practical ways to pray in all kinds of situations. Here is a prayer for elections:

I met those of our society who had votes in the ensuing election, and advised them: to vote, without fee or reward, for the person they judged most worthy; to speak no evil of the person they voted against; and to take care their spirits were not sharpened against those that voted on the other side.

The Bible offers little practical guidance about democratic elections. None of its authors had the privilege of voting for their leaders -- they were stuck with the dictators, kings, and emperors that they were given. Since voting is relatively new in human history, we have to dig into the scriptures for guidance on how to cast our ballots today.

Psalm 72 and a Virtuous Leader

Let's start with the qualities of a good leader. Even if the people of Israel did not get to choose their own king, they understood what made up an effective government. Psalm 72 specifically names some of the virtues we all long for in a leader, then and now. For one, a good leader watches out for all the people in the land: the poor (verse 12), the weak (verse 13), and the oppressed (verse 14). Meaning, a virtuous leader does not choose a certain group of people to protect and care for -- those who voted a certain way, those who are related to certain others, or those who earn a certain amount. A king who governs rightly provides care for all people by reducing violence (verse 15), and we will see the very environment respond favorably: "May there be abundance of grain in the land; may it wave on the tops of the mountains" (verse 16). Granted, a human ruler cannot make it rain, or cause the sun to shine. But the story of

Joseph in Egypt (Genesis 41) shows that a wise leader can indeed prepare for hard times, saving and storing supplies for those inevitable seasons of drought and famine. In addition, a leader who protects the poor also protects the land -- many recent studies have shown a strong connection between poverty and environmental degradation.

Joseph in Egypt (Genesis 41) shows that a wise leader can indeed prepare for hard times, saving and storing supplies for those inevitable seasons of drought and famine. In addition, a leader who protects the poor also protects the land -- many recent studies have shown a strong connection between poverty and environmental degradation. Have these qualities from Psalm 72 helped you decide? Are you clear on whom to vote for now? Or do the candidates all seem to fall short according to these standards? Well, here is some advice to consider before, during, and after you head to the polls.

Before you vote: Pray

The Book of Common Prayer provides practical ways to pray in all kinds of situations. Here is a prayer for elections:

Almighty God, to whom we must account for all our powers

and privileges: Guide the people of the United States (or of

this community) in the election of officials and representatives;

that, by faithful administration and wise laws, the rights of

all may be protected and our nation be enabled to fulfill your

purposes; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

and privileges: Guide the people of the United States (or of

this community) in the election of officials and representatives;

that, by faithful administration and wise laws, the rights of

all may be protected and our nation be enabled to fulfill your

purposes; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

This is a great outline to help you prepare to vote wisely and to pray for the United States over the weeks ahead. However, in addition to praying for the elections, you should pray for the candidates themselves. Each person running is a human being, created by God. They all have souls, and they are all redeemable. It would do us well if every Christian in America prayed that way -- for the candidates themselves and not just for a certain outcome to the elections.

When you vote: Decide

As you cast your ballot, here are four things to keep in mind:

- Experience matters. "Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much." - Luke 16:10. Granted, Jesus was not talking about political candidates here. But the principle still applies. Consider how the candidates performed in their other elected offices. If they have never been elected to something before, then you need to consider why not.

- Character matters. The Herods were a clan of leaders who ruled over Palestine and surrounding areas during the time of Jesus and the early church. Two of the Herods provide special warnings about the importance of character in a leader. The King Herod in Matthew 2 was so paranoid about being replaced that he slaughtered all baby boys that fit the description of the Messiah, as told to him by the travelling magi. In Acts 12, another Herod was struck dead because he accepted the praise and worship of people who wanted a political favor. As you vote, ask yourself: Is this candidate running for office just because he or she wants the accolades of others? This kind of self-centeredness is deadly.

- Party matters. The system of party politics in the United States ensures that a candidate's political allegiances will set the tone for how he or she governs. Regardless of what they promise to do in office, candidates are bound to follow a great deal of what their party's platform spells out. Indeed, each party spends a lot of money and effort to nominate this person. Can you vote for this candidate, as well as the people they associate with? "Whoever walks with the wise becomes wise, but the companion of fools suffers harm." -- Proverbs 13:20.

- Locality matters. Be careful when national political campaigns divide neighbors. You rely on the person who lives next door a lot more than the person in the White House. We have to work together with the people in our towns to keep the lights on, protect the safety of our drinking water, and repair our roads. When Hurricane Matthew swept through North Carolina last month, it was neighbors, local police, and first responders who helped those who were stranded. Sure, the Governor in Raleigh and the President in Washington care, but they cannot do anything to help until after dangers have passed. Samuel warned the people of Israel that a king would take their children, their produce, and their lands. Does your candidate have policies that will help rather than harm you, your neighbors, and your hometown?

After you vote: Love

As a pastor, my biggest concern is what happens after the election. Will both sides of this contest be able to come together? Specifically, will we be able to love those who voted differently than we did?

I fear that this polarizing political season has made us unloving. I'm not saying that we can't campaign for a particular candidate, nor should we not try to get our friends and neighbors to vote for the candidates we think are best qualified. I just want followers of Jesus to do so in a way that demonstrates love. Believe it or not, it is possible to be right while not acting like a jerk. I hope we can all do that as a nation beginning next week.

This is not the only time in history when God's people have lived amongst political strife, nor is America the only country to be so divided. John Wesley lived in England during a time of much political and social upheaval. Here is some advice he gave to the people called Methodists, way back in the 1770s:

I met those of our society who had votes in the ensuing election, and advised them: to vote, without fee or reward, for the person they judged most worthy; to speak no evil of the person they voted against; and to take care their spirits were not sharpened against those that voted on the other side.

Amen. May it be so.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

What is the Filioque?

Icon of the Emperor Constantine

with the bishops after the Council of Nicea

|

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified.

Over the course of a few hundred years, some churches in Latin-speaking western Europe added this one little phrase:

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son, who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified.

If your church uses this creed during its worship services, there is a good chance that it includes this "and the Son" clause, which is known by his Latin rendering: filioque. It is impossible to prove exactly how or why that phrase first got added, but it more or less became the standard practice in the West by the year 1014, which is when the influential church in Rome added it to the liturgy.

This tiny addition eventually led to the biggest split that the Christian church has ever experienced. The Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic churches had been growing apart for centuries due to cultural and linguistic differences, and they had not been treating each other very well, with the Crusades in particular creating a considerable amount of friction. But in 1054, when things finally reached a boiling point, the filioque clause was named as one of the major reasons for the so-called Great Schism. This separation still exists today, and the filioque will have to be revised before the two sides will ever consider reconciling.

The Orthodox church has good reasons for protesting the filioque. Perhaps the core issue is that no one asked them before it was added. The Creed was worked out over several decades in the fourth century, with painstaking care over specific words and phrases. As far as the East is concerned, this is an unauthorized change to one of the church's fundamental documents. Tied to this is the ongoing dispute about what a pope is authorized to do -- Orthodox churches do not have popes, and their highest leaders do not have the authority to act unilaterally (by adding phrases to the creeds).

Also, there is a fundamental theological issue at stake about how Father, Son, and Holy Spirit constitute the Holy Trinity. If the Spirit comes (proceeds) from the Father and the Son, then that seems to create a pecking order within the Godhead, with the Holy Spirit coming in last. This is a heresy, and not even Catholic or Protestant churches believe that the Holy Spirit is somehow less than the Father or the Son. Indeed, basic Christian doctrine maintains that none of the persons of the Trinity is subordinate to any of the others. The Catholic Church today claims that the filioque was never meant to say that the Holy Spirit is less than the Father or Son -- it was supposed to clarify that the Spirit is a different person than the Son, and the relationships between the three persons of the Trinity are full of mutual sharing and love. Sadly, the damage has been done, and the current Western wording of the Nicene Creed is one of the most significant issues that separate the two main branches of Christianity to this day.

Saturday, October 8, 2016

Book Review: Why Mission? by Dean Flemming

Dean Flemming writes that Christians commonly make two mistakes when it comes to mission and the scriptures: 1) they over-emphasize the Bible’s message for its original audiences, thus ignoring its power to inspire present-day mission efforts, and 2) they repeatedly rely on a few proof-texts (e.g., Matthew 28:19) to justify the need for sending out cross-cultural missionaries. Flemming suggests that both of these perspectives are too narrow, so he wrote Why Mission?, a part of the Reframing New Testament Theology series, to encourage a more holistic reading of the Bible. Specifically, he wants Christians to read the entire canon in order to see the present relevance of God’s overall mission in the world, also know as the missio Dei. Flemming’s book is thus a “missional reading” of seven New Testament books for what they both say and do -- that is, for their witness to the nature of God’s mission as revealed in the past, as well as the texts' ability to inspire mission efforts today.

Chapter 1 begins with Matthew, which Flemming calls us to “read from the back.” In other words, God’s saving work in the Old Testament only makes sense through the lens of Jesus’s life and mission. The Jesus of Matthew urges his apostles to live out Moses’s call to be the people of God, in which the tasks of evangelism and disciple-making happen within a community. Chapter 2 on Luke and Acts shows how mission is rooted in God’s nature -- the missio Dei has an especially Trinitarian -- and thus communal -- shape, with all three persons in the Godhead taking on important roles. In Luke 4:18 the Spirit-empowered Jesus, who is the recently-baptized Son of the Father, declares that God's mission is inclusive, boundary-breaking, and holistic. There are no parts of society (according to ethnic or economic divisions) or of the human being (body, mind, or soul) outside the range of God’s saving work. John’s gospel, the subject of chapter 3, delves further into the Trinitarian cooperation of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in the sending out and the drawing in of God’s people. If Matthew had prescriptive commands to “go” and “baptize,” then the fourth gospel calls Jesus’s followers to participate in a shared life that matches God’s dynamic and interactive nature. For instance, John 15 makes clear that our missional activities are first of all a call to be in God; doing mission properly flows out of a rooted and embedded life in God and in God’s community.

Philippians is the only Pauline book in Why Mission?, and the bulk of chapter 4 covers the kenosis passage of 2:6-11. Flemming calls this a “V-shaped” drama -- Jesus empties himself of power, later to be raised up and exalted by the Father. This self-emptying model calls today’s church to live from the same sacrificial posture. Chapter 5 discusses the realities involved in doing mission as an outsider -- specifically, as exiles and aliens as described in 1 Peter. Flemming sees that this epistle has important things to say to Christian minority groups today for whom Christian community is necessary for survival. For such groups, living in a community of faith is not exactly a mission strategy, although their life together becomes missional as others witness the love and commitment that are shared in the bonds of a common baptism. Chapter 6 argues that eschatology is bound up with the church’s mission, so Flemming wants to treat Revelation as more than a source for “all nations” proof-texts (for example, 7:9). The entire sweep of salvation is found in John’s Apocalypse -- creation, redemption, judgment, new creation -- and it describes the persecuted church’s challenge in staying pure while that mission is accomplished. As Flemming's Epilogue affirms, this comprehensive sweep of God’s redemptive work makes mission about more than what “missionaries” do, and even about more than what the church does. Christians are invited to participate in the missio Dei, but they do not drive it through their own cleverness, fund-raising, or strategizing.

Why Mission? provides an accessible introduction to the practice of missional reading, complementing what Christopher J.H. Wright has done (especially for the Old Testament) in The Mission of God. As an introductory-level book of 136 pages, Flemming cannot say everything that might be said, but there are a couple of missed opportunities here. For one, I would have appreciated a discussion about mission and Christendom, especially given the church's declining role in Western Europe and the US. Flemming certainly affirms that Christians are set apart in the sense of being holy (p.98), but in the chapter on 1 Peter he fails to talk about how the church's modern-day decline is leaving Christian communities less aligned with formal power structures. While the church in the US is certainly not there (yet), it may be approaching a first-century posture in relation to the government, wherein churches will become minority communities within the wider society. This is certainly already the case in many places around the world, and Peter wrote his first letter to a community in that situation. Disappointingly, Flemming avoids this opportunity, even downplaying the power differential between Christians and their first-century leaders. He states that 1 Peter’s concept of “foreignness” was “not primarily a reference to their political or social status” (p.96). Fair enough if he is countering John Elliot's strained argument that the original recipients of 1 Peter were actually a group of foreign refugees. But even without that interpretation, Peter certainly indicates that there were social and class markers that set Christians apart from the wider culture. That epistle has much to say about how to live faithfully -- that is, missionally -- as a church whose social distance varies greatly with those in power. It seems impossible to explore modern-day implications of a missional reading of the New Testament while ignoring the rise and fall of Christendom. There has never been mission without some interference from or support by government -- a fact that should have also been acknowledged in the chapter on Luke and Acts.

My second criticism stems from a personal concern about most mission-based commentaries on Philippians 2. This is a cornerstone mission text, and missionary recruiters have long called the faithful to give up their own wealth, to empty themselves of their home-country comforts, and to enter into life with the “least of these.” I’m not at all opposed to this way of framing Christian discipleship -- Paul himself uses it: “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus...” (2:5). I just do not like comparing missionaries who apply for a passport and get on a plane to Jesus, who emptied himself of heavenly privileges so that he could be born a human being. “Incarnational ministry” embraces commendable aspects of working with people who are different -- living in neighborhoods with the poor, learning local languages on the speakers’ terms, and listening to people’s expressed concerns before imposing solutions. But I do not think that living among other human beings -- no matter how great the cultural or economic chasms between missionary and host -- is at all like the divide between the heavenly realms and our own earthly reality. While I appreciate that Flemming does not necessarily invoke the “incarnational ministry” label, I wish he would have used part of chapter 4 to renounce this long-standing “missionary descent” narrative. This misreading of Philippians 2 has sustained a long-running martyr complex among cross-cultural workers for many generations.

Chapter 1 begins with Matthew, which Flemming calls us to “read from the back.” In other words, God’s saving work in the Old Testament only makes sense through the lens of Jesus’s life and mission. The Jesus of Matthew urges his apostles to live out Moses’s call to be the people of God, in which the tasks of evangelism and disciple-making happen within a community. Chapter 2 on Luke and Acts shows how mission is rooted in God’s nature -- the missio Dei has an especially Trinitarian -- and thus communal -- shape, with all three persons in the Godhead taking on important roles. In Luke 4:18 the Spirit-empowered Jesus, who is the recently-baptized Son of the Father, declares that God's mission is inclusive, boundary-breaking, and holistic. There are no parts of society (according to ethnic or economic divisions) or of the human being (body, mind, or soul) outside the range of God’s saving work. John’s gospel, the subject of chapter 3, delves further into the Trinitarian cooperation of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in the sending out and the drawing in of God’s people. If Matthew had prescriptive commands to “go” and “baptize,” then the fourth gospel calls Jesus’s followers to participate in a shared life that matches God’s dynamic and interactive nature. For instance, John 15 makes clear that our missional activities are first of all a call to be in God; doing mission properly flows out of a rooted and embedded life in God and in God’s community.

Philippians is the only Pauline book in Why Mission?, and the bulk of chapter 4 covers the kenosis passage of 2:6-11. Flemming calls this a “V-shaped” drama -- Jesus empties himself of power, later to be raised up and exalted by the Father. This self-emptying model calls today’s church to live from the same sacrificial posture. Chapter 5 discusses the realities involved in doing mission as an outsider -- specifically, as exiles and aliens as described in 1 Peter. Flemming sees that this epistle has important things to say to Christian minority groups today for whom Christian community is necessary for survival. For such groups, living in a community of faith is not exactly a mission strategy, although their life together becomes missional as others witness the love and commitment that are shared in the bonds of a common baptism. Chapter 6 argues that eschatology is bound up with the church’s mission, so Flemming wants to treat Revelation as more than a source for “all nations” proof-texts (for example, 7:9). The entire sweep of salvation is found in John’s Apocalypse -- creation, redemption, judgment, new creation -- and it describes the persecuted church’s challenge in staying pure while that mission is accomplished. As Flemming's Epilogue affirms, this comprehensive sweep of God’s redemptive work makes mission about more than what “missionaries” do, and even about more than what the church does. Christians are invited to participate in the missio Dei, but they do not drive it through their own cleverness, fund-raising, or strategizing.

Why Mission? provides an accessible introduction to the practice of missional reading, complementing what Christopher J.H. Wright has done (especially for the Old Testament) in The Mission of God. As an introductory-level book of 136 pages, Flemming cannot say everything that might be said, but there are a couple of missed opportunities here. For one, I would have appreciated a discussion about mission and Christendom, especially given the church's declining role in Western Europe and the US. Flemming certainly affirms that Christians are set apart in the sense of being holy (p.98), but in the chapter on 1 Peter he fails to talk about how the church's modern-day decline is leaving Christian communities less aligned with formal power structures. While the church in the US is certainly not there (yet), it may be approaching a first-century posture in relation to the government, wherein churches will become minority communities within the wider society. This is certainly already the case in many places around the world, and Peter wrote his first letter to a community in that situation. Disappointingly, Flemming avoids this opportunity, even downplaying the power differential between Christians and their first-century leaders. He states that 1 Peter’s concept of “foreignness” was “not primarily a reference to their political or social status” (p.96). Fair enough if he is countering John Elliot's strained argument that the original recipients of 1 Peter were actually a group of foreign refugees. But even without that interpretation, Peter certainly indicates that there were social and class markers that set Christians apart from the wider culture. That epistle has much to say about how to live faithfully -- that is, missionally -- as a church whose social distance varies greatly with those in power. It seems impossible to explore modern-day implications of a missional reading of the New Testament while ignoring the rise and fall of Christendom. There has never been mission without some interference from or support by government -- a fact that should have also been acknowledged in the chapter on Luke and Acts.

My second criticism stems from a personal concern about most mission-based commentaries on Philippians 2. This is a cornerstone mission text, and missionary recruiters have long called the faithful to give up their own wealth, to empty themselves of their home-country comforts, and to enter into life with the “least of these.” I’m not at all opposed to this way of framing Christian discipleship -- Paul himself uses it: “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus...” (2:5). I just do not like comparing missionaries who apply for a passport and get on a plane to Jesus, who emptied himself of heavenly privileges so that he could be born a human being. “Incarnational ministry” embraces commendable aspects of working with people who are different -- living in neighborhoods with the poor, learning local languages on the speakers’ terms, and listening to people’s expressed concerns before imposing solutions. But I do not think that living among other human beings -- no matter how great the cultural or economic chasms between missionary and host -- is at all like the divide between the heavenly realms and our own earthly reality. While I appreciate that Flemming does not necessarily invoke the “incarnational ministry” label, I wish he would have used part of chapter 4 to renounce this long-standing “missionary descent” narrative. This misreading of Philippians 2 has sustained a long-running martyr complex among cross-cultural workers for many generations.

Saturday, October 1, 2016

We Do What We Think, or We Think What We Do?

Common sense teaches us that we do things based on what we think or how we feel. That is certainly true, but we don't often consider how human nature also works in the opposite direction -- that we think and feel things because our habits and activities have trained us to. According to this second view, our actions are rehearsals for the people we will become. Here are two recent scientific studies that prove that what we do can shape our thoughts and feelings, for better or worse.

The Lancet journal published results of a study that provided "baby bots" to teen girls in Australia. These realistic dolls were programmed to cry when they needed to be rocked, changed, or fed. The program had the exact opposite results as expected -- instead of scaring these girls away from sexual activity, the teens who received a doll were actually more likely to be sexually active, have an abortion, or give birth than the ones who did not. The scientists who ran the study were puzzled as to why, but I have my own theory: caring for the dolls was a rehearsal for being a mother. Changing diapers, feeding, and rocking the dolls prepared the girls to have their own children, so their motivation to prevent a pregnancy was lower. (In addition, the girls in the program were part of a community -- they attended sessions and support groups with others. Having a doll was in fact fun -- far from being an isolating or lonely experience.)

In a separate study, researchers showed that music lessons can make children less aggressive. Students in Germany who took private lessons for a year and a half were less likely to be provoked than children who studied science for the same length of time. As someone who sat through weekly piano lessons beginning at age 10, I can testify to the calming effect of one-on-one music instruction. I specifically remember thinking, around the age of 14, that I had grown much more patient in the previous year. Sitting quietly in a piano studio with a teacher for 30 minutes a week was a very different activity than anything else I did as a teenager. Concentrating in the stillness actually helped me think and read better in school.

These findings are no small thing to worship leaders and pastors. I have written about the importance of children's participation in worship, and I take these two studies as further proof that the activities in our services can and should actually shape us all into better human beings. Corporate prayer, singing, and listening make us more patient and hopeful, training us to be tuned to what God is doing in the world. Those of us responsible for leading worship need to remember the formative aspects of our services. It is important that members of the congregation actually get to do things that change them for the better.

|

| Photo from website link on the right |

|

| Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images |

These findings are no small thing to worship leaders and pastors. I have written about the importance of children's participation in worship, and I take these two studies as further proof that the activities in our services can and should actually shape us all into better human beings. Corporate prayer, singing, and listening make us more patient and hopeful, training us to be tuned to what God is doing in the world. Those of us responsible for leading worship need to remember the formative aspects of our services. It is important that members of the congregation actually get to do things that change them for the better.

Saturday, September 24, 2016

What Do Bishops Do?

Perhaps you first heard the word "bishop" when you learned how to play chess. The bishop pieces, set on each side of the royal couple, can move diagonally for an unlimited number of spaces across the board. Of course the pieces on a chess board represented real-life roles in medieval Europe, but the job of a bishop is still a modern one. Not all varieties of churches call their leaders bishops, but the United Methodist Church does. This post presents a brief explanation of a bishop's role.

There is some -- but not much -- biblical evidence that the title of bishop was used by the end of the New Testament period. The Greek word episkopos shows up in a few instances, but it probably did not mean what bishop does today -- it was almost definitely not an official title back then. Most English translations do not even translate episkopos as "bishop" in every occurrence in the New Testament. Take the NRSV:

When the American Methodists decided to have bishops, that made them an episcopal denomination, hence their initial name: The Methodist Episcopal Church. Although it has undergone many splits and mergers over the past two centuries, the MEC's heir, the United Methodist Church, remains a church with bishops. So what do these men and women do exactly?

The American Methodists built their denomination in the image of their newly-forming federal government. There are three branches of the UMC, set up in a system of checks and balances. The General Conference meets every four years and creates the laws of the church, codified in the Book of Discipline. The bishops act as executives of those rules, charged with carrying out their mandates. A judicial council serves as the third branch, interpreting the rules to ensure that they are consistent with the foundational doctrines of the denomination.

United Methodist bishops are elected and appointed to four-year terms by Jurisdictional and Central Conferences, which are regional groupings consisting of representatives from several Annual Conferences. Bishops serve four-year terms, and they are usually moved to another area after 2 consecutive terms in the same place. In many places, such as the Raleigh Episcopal Area where I work, one bishop is over one Annual Conference. However, there are some bishops who are appointed to serve over more than one Annual Conference at a time. For instance, in the Philippines a bishop might have to preside over as many as 12 Annual Conferences.

There is some -- but not much -- biblical evidence that the title of bishop was used by the end of the New Testament period. The Greek word episkopos shows up in a few instances, but it probably did not mean what bishop does today -- it was almost definitely not an official title back then. Most English translations do not even translate episkopos as "bishop" in every occurrence in the New Testament. Take the NRSV:

- Acts 20:28 - Keep watch over yourselves and over all the flock, of which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to shepherd the church of God that he obtained with the blood of his own Son

- 1 Timothy 3:2-3 - Now a bishop must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money.

- Philippians 1:1 - Paul and Timothy, servants of Christ Jesus, To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi, with the bishops and deacons.

Back in Paul's day, his idea of a bishop was probably something closer to "elder" or "pastor" -- a spiritual leader within a local congregation who preached, led worship, kept the believers connected to each other, and prevented false teaching. Our current concept of a bishop as someone who supervises several pastors and multiple congregations came later, after Christianity grew and the faith spread.

The Methodist Church grew out of the Church of England in the 18th century, which had an episcopal system -- that is, they had a hierarchy consisting of bishops who oversaw the work of the wider church. John and Charles Wesley, two of Methodism's main founders, were priests in the Anglican church, and they (originally) had no intention of creating a new denomination outside of their own. However, when Methodism spread to the colonies, the Americans had very little desire to worship in the state church of the king they were trying kick out of their lands. So, out of expediency, John Wesley consecrated Thomas Coke and Frances Asbury as superintendents over the new churches in America. Soon after these men arrived in the colonies, the American Methodists decided to refer to Coke and Asbury as bishops. This was no small thing to Wesley, who recognized that -- not being a bishop himself -- he could not consecrate new bishops. To this day, that break in the line of succession, in which Coke and Asbury were not set apart by an official bishop, still marks a formal break between the Episcopal and United Methodist Churches.

|

| Asbury is consecrated in 1784 |

The American Methodists built their denomination in the image of their newly-forming federal government. There are three branches of the UMC, set up in a system of checks and balances. The General Conference meets every four years and creates the laws of the church, codified in the Book of Discipline. The bishops act as executives of those rules, charged with carrying out their mandates. A judicial council serves as the third branch, interpreting the rules to ensure that they are consistent with the foundational doctrines of the denomination.

United Methodist bishops are elected and appointed to four-year terms by Jurisdictional and Central Conferences, which are regional groupings consisting of representatives from several Annual Conferences. Bishops serve four-year terms, and they are usually moved to another area after 2 consecutive terms in the same place. In many places, such as the Raleigh Episcopal Area where I work, one bishop is over one Annual Conference. However, there are some bishops who are appointed to serve over more than one Annual Conference at a time. For instance, in the Philippines a bishop might have to preside over as many as 12 Annual Conferences.

What many United Methodists understand about bishops is their ability to appoint and remove pastors from local churches. This system of itineracy has been a characteristic mark of Methodism from the beginning, all the way back to the days of circuit-riding preachers on horseback. In my opinion, this is one of the great advantages of United Methodism. Churches, as well as their pastors, are accountable to a larger body, with support systems available to those are struggling or need help.

Americans have always been wary of autocratic leaders, so there are certain things United Methodists do not allow their bishops to do. For example, even thought they preside over the meetings, bishops do not have a vote at any conferences -- Annual, Jurisdictional, or General. Also, while it is their own hands placed on the heads of new Elders and Deacons, bishops do not decide who the church ordains -- that is the job of the Board of Ordained Ministry in each Annual Conference.

There is much more to the role of bishop in the United Methodist Church. For additional information, check out this website from the denomination (click here), Chapter 6 in Laceye Warner's book The Method of our Mission, or paragraphs 46-54 in the Book of Discipline.

Americans have always been wary of autocratic leaders, so there are certain things United Methodists do not allow their bishops to do. For example, even thought they preside over the meetings, bishops do not have a vote at any conferences -- Annual, Jurisdictional, or General. Also, while it is their own hands placed on the heads of new Elders and Deacons, bishops do not decide who the church ordains -- that is the job of the Board of Ordained Ministry in each Annual Conference.

There is much more to the role of bishop in the United Methodist Church. For additional information, check out this website from the denomination (click here), Chapter 6 in Laceye Warner's book The Method of our Mission, or paragraphs 46-54 in the Book of Discipline.

Saturday, July 2, 2016

What Tennis Taught Me About Preaching

There is a discipline to preaching every Sunday morning. Like many things in life, the more you do it, the better you get. I also maintain another weekly ritual where the same principle applies -- Saturday morning tennis. The two activities are not that all that different, from a mental perspective, sharing more similarities than "practice makes perfect." In fact, I have learned a lot about preaching by thinking about my strengths and weaknesses on the tennis court.

When I lived in Manila, I hired a retired tennis pro to work out with me once a week. At 6:00am every Saturday morning my coach would warm me up with drills for 30 minutes before he and I played a set or two. On the rare occasions when he couldn't make it, and I would just play a match against a friend, it felt like something was missing. Preaching is the same way, in that the sermon is just one part of a worship service, one that happens within a liturgy of other important moments -- both before and after the proclamation of the Word. The sermon doesn't have to "say" everything -- there are hymns, prayers, readings, testimonies, and songs that can lead people into God's presence. That's why it doesn't feel right when I have to preach in class as an assignment; I just stand up, read the scripture, pray, and go to it. It is like playing a set of tennis without warming up first.

My tennis coach did more demonstrating than explaining. The tenor of his teaching style was "more with less." I can still remember my first lesson with him. I was all over the place, taking way too many steps on my approach, utilizing some kind of crazy-looking back-swing. Not even 5 minutes into the lesson he stopped and used his let-me-show-you-how method, mimicking my flailing arms and legs so I could see how I was working twice as hard as necessary. According to his demonstrations, a good tennis player knows where the ball is going, gets there efficiently, and gets ready for the opponent's return shot -- all with as few steps as possible. My preaching has gone through a similar metamorphosis. Maybe it was because I was so eager, or maybe I had been building up to this call all these years, but my first sermons had enough points for an additional 1 or 2 sermons. My congregations were gracious, but I was wearing them out. Remembering my tennis lessons helped me see that I was preaching with a lot of unfocused energy, adding too much material to each message. Lately I've been getting better at figuring out just what I need to say, saying it well, and stopping.

At first I didn't get my coach's "show me" style of teaching. It wasn't until I read The Inner Game of Tennis that I began to appreciate his quietness, in which Tim Gallwey used principles from Buddhism to enhance his concentration on the court. His main discovery was that the chattering in his head prevented him from hitting the ball well. These voices of self-evaluation ("That was a weak shot"... "No wonder that went in the net. Look at the grip you were using.") distracted him from what he really needed to be addressing -- namely, the ball. Anne Lamott is an author who used to play tennis on the junior circuit. She says that writers also suffer from these chattering, secondary voices that distract from actually getting down to the task of writing. There are just too many details in tennis -- as in writing or preaching -- to hold in one's conscious mind, and she says that trying to process all of them simultaneously is paralyzing. So clearing one's head of the noise is crucial to stop this crazy-making second-guessing. Gallwey wants his readers to keep their eyes on the ball, concentrating only on that, thereby preventing the tennis player from over-thinking other details. I am similarly learning to focus on where I'm going to land my sermon. They say Rafael Nadal thinks 3 or 4 shots ahead when he's playing a match. He knows where he wants the point to go, usually setting things up so that he can finish off with his massive forehand. If I know where my sermon is going, I stay on track and don't let a lot of extra words -- either the ones that I'm saying, or the ones in my head -- get me distracted from the message.

There are one hundred other things to consider while preaching: Am I going too fast? Where are my hands? Did I just mispronounce Melchizedek? (Yep, I just did.) Richard Lischer wrote in The End of Words that preaching is not really about our words; it is about the ultimate purpose of God's salvation history: the reconciliation of all things through and in Christ (2 Corinthians 5:19, Colossians 1:20-22). Lischer applies the same "more with less" principle to preaching, emphasizing a moment that he calls the "focal instance." This is in contrast to the traditional sermon illustration that sometimes we remember more than the sermon's main point. Lischer warns that preachers can work up their own stories so that they stand out more than the gospel itself. A focal instance still describes important points, but it weeds out unnecessary details that distract from the central focus.

I have learned to make errors boldly. It is more fun to aim for the lines than to take an easy shot down the middle. Similarly, I've learned to be bolder in my preaching, no longer cautiously trying to make easy points safely in the center of the court. Congregations want a preacher to be confident, and they will return that confidence when they sense it.

Finally, you cannot prepare for all aspects of a given match. As a tennis player, you have to react to specific circumstances -- your opponent's service, the weather, your sore shoulder, etc. In preaching you can only prepare so much, because the word for that day also has to respond to the moment. I'm learning to prepare my sermons so that my peak interest and energy arrives on Sunday morning. If I prepare too much too early, then I just end up reading a message that doesn't hit where people are. Being "ready to go" on Sunday means that I'm still wrestling with the text myself as I stand up to preach it.

Saturday, June 11, 2016

Burnout & Work-Life Balance

Back in the 1990s, when I was preparing for a career in cross-cultural mission, I was taught -- mostly implicitly -- that the main enemy of the missionary was not spiritual warfare, or typhoid, or angry natives. Instead, the primary destroyer of God's plan for the evangelization of the nations was missionaries' work schedules; our real opponent was burnout.

Don't get me wrong: burnout is a real thing, and I've seen it cause real distress in people's lives. (If you need help, click here for resources on burnout.) I'm just not convinced that it is the major problem contributing to missionary attrition or lack of effectiveness. If truth be told, I witnessed a lot of under-work in the field -- 20-hour work weeks and frequent, extended breaks that amounted to weeks-long vacations -- in the name of "personal care."

We were taught to carve out lots of downtime, preserving ourselves for the long haul; our trainers urged habits like quitting work at a certain hour each day, taking regular days off, and going on frequent vacations. This isn't bad advice in itself, but it aims to solve the wrong problem. After more than a decade of mission experience, I have come to think that the main issue around burnout is not about how many hours one puts in at work. Rather, it has to do with a sense of connection one has with that work (and especially relationships with co-workers). In other words, working 60 hours a week will not necessarily lead you to burn out, and limiting yourself to 4-hour days may not prevent it.

It's not only missionaries who talk about limiting work as the answer to burnout. Our society at large makes the same claim when we use the phrase "work-life balance." I find this to be an inherently unhelpful formulation, one I try to never use. I'm not enough of a fundamentalist to disdain concepts simply because they "are not in the Bible." However, "balance" is a value in Star Wars, not Christianity. Jesus Christ did not come in flesh, die on the cross, and overcome death out of some desire by God to restore balance. Rather, Christ's work is to gather up all things and bring them together in healing and reconciliation. (Check out Colossians 1:15-23.) Talk of balancing our schedules -- making sure we spend just enough time on everything -- is simply a capitulation to the broken time that we inhabit in this fallen era that is on a stop-watch driven, ticking-away march toward death. God has something better in store -- a different kind of time that is, at least partially, revealed to us in the scriptures as an expectancy-laden, life-giving, pulsing-with-light reality that will go on without end in the heavenly reign of Christ.

God isn't interested in balancing your life. God wants to overwhelm it -- wrapping up and ruling over your relationships, your work, your money, your family...everything. I'm not saying that missionaries shouldn't take breaks, or that pastors should work harder. My prayer is simply that all who labor will find their rest in Christ's overwhelming, bundling-up, gathering-together love.

|

| "We're pacing ourselves." |

We were taught to carve out lots of downtime, preserving ourselves for the long haul; our trainers urged habits like quitting work at a certain hour each day, taking regular days off, and going on frequent vacations. This isn't bad advice in itself, but it aims to solve the wrong problem. After more than a decade of mission experience, I have come to think that the main issue around burnout is not about how many hours one puts in at work. Rather, it has to do with a sense of connection one has with that work (and especially relationships with co-workers). In other words, working 60 hours a week will not necessarily lead you to burn out, and limiting yourself to 4-hour days may not prevent it.

It's not only missionaries who talk about limiting work as the answer to burnout. Our society at large makes the same claim when we use the phrase "work-life balance." I find this to be an inherently unhelpful formulation, one I try to never use. I'm not enough of a fundamentalist to disdain concepts simply because they "are not in the Bible." However, "balance" is a value in Star Wars, not Christianity. Jesus Christ did not come in flesh, die on the cross, and overcome death out of some desire by God to restore balance. Rather, Christ's work is to gather up all things and bring them together in healing and reconciliation. (Check out Colossians 1:15-23.) Talk of balancing our schedules -- making sure we spend just enough time on everything -- is simply a capitulation to the broken time that we inhabit in this fallen era that is on a stop-watch driven, ticking-away march toward death. God has something better in store -- a different kind of time that is, at least partially, revealed to us in the scriptures as an expectancy-laden, life-giving, pulsing-with-light reality that will go on without end in the heavenly reign of Christ.

God isn't interested in balancing your life. God wants to overwhelm it -- wrapping up and ruling over your relationships, your work, your money, your family...everything. I'm not saying that missionaries shouldn't take breaks, or that pastors should work harder. My prayer is simply that all who labor will find their rest in Christ's overwhelming, bundling-up, gathering-together love.

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Don't Give Up Your Art

In the 1981 film Chariots of Fire, the sister of British Olympian Eric Liddell urged her brother to give up an athletic career for the sake of his "true" calling -- serving as a cross-cultural missionary. He resisted her either-or thinking by insisting that there was more than one way for him to glorify God. To Liddell, serving the Lord should not require him to give up his greatest gift: "I believe that God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. When I run, I feel his pleasure."

Athletes aren't the only ones who are presented with this unfortunate choice between gifting and God's will. Over the years I have encountered many artists who were similarly compelled to set aside talents in music, dance, or visual arts so that they could pursue a career in ministry. It breaks my heart to hear how often young people come to understand Christin vocation in terms of this stark binary -- it's either God's will for your life, or your art. In Many Beautiful Things, a recent movie about English painter Lilias Trotter, the protagonist's decision is portrayed in the same way: she decided to serve the Lord in North Africa, relegating herself to obscurity, and thereby forsaking the potential to be England's best living artist. (This is one of her watercolors. Also, see the movie trailer at the bottom of this post, or at this link.)

About 25 years ago, as a freshman at Asbury University, I also felt caught between two choices. My major was Christian Mission, but I was also pursuing a minor in Music. To some people -- including myself at times -- it seemed like I couldn't make up my mind. Was I going to pursue mission or music? It was a choice I didn't want to make, one that seemed false, requiring me to either give up my calling to cross-cultural ministry or set aside my (modest) God-given abilities in music. So it was with much gratitude that I learned about ethnomusicology -- more specifically, that the study of music and culture was a discipline being used in mission work, under the umbrella of what would one day be called ethnodoxology. Thankfully, this discovery came early in my college life, so I did not have to live in the tension between two choices for very long. While the world is different now that it was in the 1800s, presenting more opportunities than what was available for Liddell or Trotter, there are still artists today who forsake their gifts in order to pursue a career in ministry.

Athletes aren't the only ones who are presented with this unfortunate choice between gifting and God's will. Over the years I have encountered many artists who were similarly compelled to set aside talents in music, dance, or visual arts so that they could pursue a career in ministry. It breaks my heart to hear how often young people come to understand Christin vocation in terms of this stark binary -- it's either God's will for your life, or your art. In Many Beautiful Things, a recent movie about English painter Lilias Trotter, the protagonist's decision is portrayed in the same way: she decided to serve the Lord in North Africa, relegating herself to obscurity, and thereby forsaking the potential to be England's best living artist. (This is one of her watercolors. Also, see the movie trailer at the bottom of this post, or at this link.)

About 25 years ago, as a freshman at Asbury University, I also felt caught between two choices. My major was Christian Mission, but I was also pursuing a minor in Music. To some people -- including myself at times -- it seemed like I couldn't make up my mind. Was I going to pursue mission or music? It was a choice I didn't want to make, one that seemed false, requiring me to either give up my calling to cross-cultural ministry or set aside my (modest) God-given abilities in music. So it was with much gratitude that I learned about ethnomusicology -- more specifically, that the study of music and culture was a discipline being used in mission work, under the umbrella of what would one day be called ethnodoxology. Thankfully, this discovery came early in my college life, so I did not have to live in the tension between two choices for very long. While the world is different now that it was in the 1800s, presenting more opportunities than what was available for Liddell or Trotter, there are still artists today who forsake their gifts in order to pursue a career in ministry.

At first I thought that my calling to mission work meant that I would have to forget about being a musician. I only knew about two distinct tracks for those called to ministry: word-based ministries for pastors and missionaries, and arts-based work for worship leaders. It felt like choosing one over the other would have been a major loss. So when I discovered a way to blend the two tracks -- that is, to bring my music background into cross-cultural ministry, I did not question whether or not God was behind it. When I learned that mission-focused ethnomusicology offered a way of doing both “word” and “arts” ministries together, I did not have to pray about signing up. This revelation was an answer to prayer, not something to go on the prayer list. I imagine Bezalel responded to Moses’s commission in the same way; he didn't have to say anything because working with wood, stone, and gold was exactly what he was supposed to do.

Friday, May 20, 2016

How to Write a Book Review

In addition to my two primary occupations -- as a theology student and a pastor of two churches -- I also serve as the Reviews Editor for the journal Global Forum on Arts and Christian Faith. Book review essays are among my favorite kinds of writing, so I would like to offer some advice for reviewers who might want to (or be asked to) write one of their own.

First of all, there is no formula for writing an engaging review of a book (or a film, art exhibit, or performance). Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that no one wants to read a formulaic review. However, like all art forms -- and yes, reviewing and critiquing are forms of art -- there are certain conventions to consider when composing a review essay.

So, why do we write book reviews at all? Because we want better books. A.O. Scott, film critic for the New York Times, wrote recently that critics are not the enemies of artists, nor are they parasites who feed off of creative types. Critics are actually artists in their own right, trying to improve society's output of art. Go make the world a better place and write a critical review of a book you just read. If it's about worship or art and culture, send me a message and ask about putting it in our journal.

First of all, there is no formula for writing an engaging review of a book (or a film, art exhibit, or performance). Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that no one wants to read a formulaic review. However, like all art forms -- and yes, reviewing and critiquing are forms of art -- there are certain conventions to consider when composing a review essay.

- List the title, author, year of publication, publisher, and number of pages. This is all standard stuff that usually comes at the beginning of the review. A good editor will ask you for it if you forget to submit it with your draft.

- Include a quote from the book. Part of your job as a reviewer is to describe the author's main point(s). This can (usually) be accomplished by quoting the thesis, or a supporting argument, directly from the book. Don't make it too long -- a sentence or two is probably adequate.

- Tell us what you think. A review is not simply a report or summary of what the book says. That's what dust jackets are for, and a de-personalized summary of a book's main points is not fun reading. Your job as a reviewer is to converse with the author based on your own experiences and viewpoints. This is why you don't have to know more about the subject than the author -- you just need to relate it to your own personal knowledge in interesting ways. But don't go overboard -- no one (besides your own mother) wants to read a review that is mostly about you.

- Place the book in an intellectual landscape. Be sure to mention what kind of book is being reviewed, such as which genre it belongs to -- e.g., systematic theology, ethnography, fiction, poetry, etc. Go a step further, thereby creating a stronger review, by placing this book in relation to other books -- that is, describe how it is similar to or different from well-known works in the same field. For instance, if the author studied at a prominent university with famous professors, then establishing their academic pedigree might help your readers better understand the book's perspective. Also, if the book is theological in nature, then you might mention where the author studied and/or which faith tradition she belongs to. In other words, your ability to frame the book within a universe of ideas will greatly increase the value of your review. This is essentially why I read book reviews. It's not only that I lack the time to read every book that I want (or need) to. I also want to know how various schools of thought are developing and who is contributing to them.

- Combine more than one book. A multiple-book review is a great way to situate a book within a wider academic framework. Placing two or three (or more) books in conversation with each other exposes and clarifies the different intentions of the various authors. Also, you might consider pairing a theoretical book with one focused on practical matters, testing whether the ideas in the former support the recommendations in the latter.

- Read other reviews, especially of the book(s) you are writing about. Don't reinvent the wheel; make sure you aren't writing a review that someone else already has. Also, other reviewers will spark ideas and draw out things that you didn't notice on your first reading. Here are some publications who put out excellent review essays for a general audience:

Christ and Pop Culture

In addition, every academic field has its own journals that include thoughtful and critical reviews of new academic books. You might need access to a library or a subscription to read those, and scholarly reviews may take years to come out (instead of weeks for popular books).

The Curator

Books and Culture

New York Times Sunday Book Review

- Mention where the book succeeds and where it fails. You aren't a Roman Emperor who gets to decide whether the author lives or dies. So your review should be more nuanced than "liked it" or "didn't like it." The book did at least one thing right, and there was something it could have done better. Point out examples of each. Better yet, tie your praises and criticisms to something you have noticed in your own experience.

So, why do we write book reviews at all? Because we want better books. A.O. Scott, film critic for the New York Times, wrote recently that critics are not the enemies of artists, nor are they parasites who feed off of creative types. Critics are actually artists in their own right, trying to improve society's output of art. Go make the world a better place and write a critical review of a book you just read. If it's about worship or art and culture, send me a message and ask about putting it in our journal.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

What is General Conference?

United Methodists like to meet, or -- in the official language -- "to conference." (Yes, I'm using that word as a verb.) We have charge conferences every year for each local church to name its officers and committee chairs and set pastors' salaries. Our primary administrative units are called annual conferences, showing that the UMC's organizational

structure is based on what happens at these yearly face-to-face gatherings where laity and clergy gather to worship and make decisions. But as an entire denomination, the United Methodist Church only does it's official business at a set of meetings that occur every four years -- an event called General Conference.

It is easy to remember what years General Conference happens -- it's always the same as the US Presidential election and the Summer Olympics. Milestones in the life of the United Methodist Church (and the Methodist Church before we became "United") are marked by conference years:

This General Conference is being hosted in Portland, Oregon on May 10-20. The theme is 'Therefore, Go', based on the Great Commission of Matthew 28.

I understand that we will be able to watch the sessions online once things get underway in Portland. In the meantime, and throughout, I would encourage all United Methodists to pray for the proceedings. See this website for prayer resources: http://60daysofprayer.org/ While the details can get quite technical, the business of General Conference is important.

structure is based on what happens at these yearly face-to-face gatherings where laity and clergy gather to worship and make decisions. But as an entire denomination, the United Methodist Church only does it's official business at a set of meetings that occur every four years -- an event called General Conference.

It is easy to remember what years General Conference happens -- it's always the same as the US Presidential election and the Summer Olympics. Milestones in the life of the United Methodist Church (and the Methodist Church before we became "United") are marked by conference years:

- 1744 - John Wesley has his first meeting of Methodist preachers to set guidelines for the new movement.

- 1784 - First conference for American Methodists. Francis Asbury is set apart as a Superintendent, a title he later changed to Bishop.

- 1956 - Full clergy rights were granted to women pastors.

- 1968 - The United Methodist Church was officially created from a merger of several denominations.

Even our main denominational publications, such as the United Methodist Hymnal, are approved at General Conference. (Our current hymnal was voted on in 1988.)

But the main books that come out of General Conference are our official rulebook -- The Book of Discipline -- and our official policy statements -- The Book of Resolutions. No other group, and no individual, can speak for the denomination; General Conference is the only official voice of the church.

The 864 delegates to General Conference, equally divided between clergy and laity, sent by their respective annual conferences, are expected to vote on something like 1044 petitions over 10 days. Delegates come from every place in the world where United Methodist churches are established -- it is truly a worldwide gathering, with people from the Philippines, Africa, and Europe joining the US delegates.

This General Conference is being hosted in Portland, Oregon on May 10-20. The theme is 'Therefore, Go', based on the Great Commission of Matthew 28.

I understand that we will be able to watch the sessions online once things get underway in Portland. In the meantime, and throughout, I would encourage all United Methodists to pray for the proceedings. See this website for prayer resources: http://60daysofprayer.org/ While the details can get quite technical, the business of General Conference is important.

Saturday, April 9, 2016

What the Church Can Learn from Drug Addicts

Fresh Air host Terry Gross recently interviewed Tracey Helton Mitchell about her book The Big Fix: Hope After Heroin. In the 1990s Mitchell was strung out on black tar heroin, living on the streets as she sought various ways to get high. She was even featured in the HBO documentary The Dark End of the Street, which you can watch at the link at bottom of this post.

Today Mitchell is sober and, besides being an author, works as a treatment counselor, helping others get clean. A couple of things struck me from her Fresh Air interview:

Today Mitchell is sober and, besides being an author, works as a treatment counselor, helping others get clean. A couple of things struck me from her Fresh Air interview: